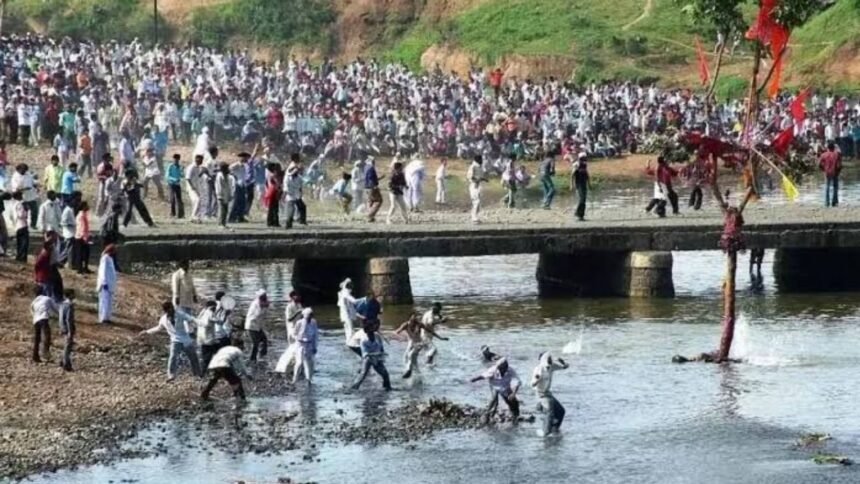

Police patrols cut their way through the masses, standing on two sides of the Jam River. At 10 am, stones begin to fly between Pandhurna and Sawargaon – aimed precisely at the other side.

On Saturday, over 900 people were injured in the ritualistic Gotmar fair stone-pelting in the area between Pandhurna town and the neighbouring Sawargaon village. Aimed at commemorating a tragic love story, the centuries-old Gotmar fair in Madhya Pradesh’s Pandhurna district continues despite injuries and attempts to ban it.

The state had prepared for this – over 600 police personnel were deployed from Chhindwara, Betul, Seoni, Narsinghpur, and Pandhurna at 47 checkpoints, drones and CCTVs monitored movement, and 25 doctors, 200 paramedics and 16 ambulances waited in six makeshift health centres along the bank.

Still, as the area turned into a battlefield, chaos was unavoidable. Men staggered with bloodied heads, women carried the wounded to waiting stretchers, and the ambulance sirens drowned out the festive drums.

Superintendent of Police (Pandhurna) Sundar Singh told The Indian Express that every year, more than 700 people get injured in this festival.

“This time 934 people were injured. This is because a large number of people turned up. No deaths were reported this time, which is a win for us. The last time a death happened in this festival was in 2023. At least 15 people have historically died in this festival,” he said.

Attempts to ban the festival a few years ago had failed, he said.

Story continues below this ad

“Then we started seeing that people began stone-pelting in secret and people getting injured. So, we had to involve all the community leaders and restart the festival. We have deployed adequate security officials to ensure the law-and-order situation holds up. Our mission is to make sure not a single person dies,” he said.

The Gotmar festival traces its origins to a legend passed down through generations. As the legend goes, a young man from Pandhurna once attempted to elope with a woman from Sawargaon, across the Jam. The villagers of Sawargaon, determined to stop him, rained stones from the opposite bank. Pandhurna too retaliated with stones. The couple’s fate has been lost to history but the confrontation was ritualised into an annual battle, carrying forward as a matter of honour, identity, and rivalry.

In the modern-day festival, residents of the two villages pelt stones at each other as they race to snatch a flag atop a dead tree in the middle of the river.

For many, the festival is not just a spectacle but an inheritance, with many travelling down from other parts of the country to see it.

Story continues below this ad

“I come here every year to witness this festival of stone pelting,” Lata Wankhede, who travelled from Pune with a group of women, said. “It was stopped for a time but was restarted. It’s up to God now to ban this festival or not.”

But others marvel at its survival. “I saw some men being carted into ambulances with torn heads, and some others dodge flying stones. It’s amazing to see police allow this festival,” Kamlesh Wankhede, a tourist from Nagpur, said.

Yet behind the spectacle lies a trail of loss. Since 1955, at least 13 people have died during Gotmar. For their families, the festival is a grim reminder of these deaths.

One of these is Ashu Sarkade, whose uncle died in the mela in 1978. “We don’t want Gotmar to continue but it’s tradition. The problem is when people consume large amounts of liquor and participate in this festival,” she said.

Story continues below this ad

In Savargaon, Ramesh Sambare lost his brother on August 24, 1987. He remembers how firing broke out during the clashes that year, and tear gas filled the air.

During the chaos, his brother Kothiram was struck by a bullet. “Seeing him in a pool of blood, I cried,” Ramesh said. “Another relative too was killed during Gotmar.”

For the Chaure family, August 31, 1989, remains etched in memory. That evening, Narayan Chaure attempted to climb and retrieve the ceremonial flag that marks the festival’s conclusion. As he did, stone-pelting resumed. He fell into the river and later died in hospital. “The scene still haunts me,” his brother Yogiraj Chaure said.

Every year, officials attempt to curb the violence. Chhindwara Collector Ajay Dev Sharma imposed Section 144 this year and insists the administration is committed to preventing fatalities. “We have told the people that the aim of the festival is not to attack others and injure them. Adequate police and medical staff have been deployed to ensure there are no deaths,” he said.